Tagged: Cooperstown

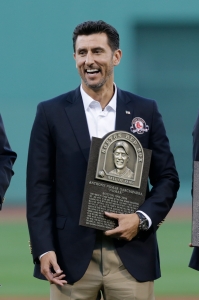

Nomar: the Hall of Fame career that wasn’t

From: The Boston Globe

The drumbeat of Pedro Martinez’s Hall of Fame candidacy resounded with the same air of anticipation and inevitability that accompanied a two-strike count when he occupied his stage at Fenway Park. The opportunity to reflect on his career is as much visceral and emotional as it is statistical; to remember Martinez on the mound is to recall a spectacle rarely matched, the unusual experience in which all parties – fans, hitters, the pitcher himself – knew that greatness and artistry were transpiring.

The drumbeat of Pedro Martinez’s Hall of Fame candidacy resounded with the same air of anticipation and inevitability that accompanied a two-strike count when he occupied his stage at Fenway Park. The opportunity to reflect on his career is as much visceral and emotional as it is statistical; to remember Martinez on the mound is to recall a spectacle rarely matched, the unusual experience in which all parties – fans, hitters, the pitcher himself – knew that greatness and artistry were transpiring.

Yet for a time, as brilliant as Martinez was, he did not stand alone in Boston atop a baseball Olympus. For a time, Martinez enjoyed a peer whose performances nearly matched the pitcher for brilliance. Yet the fact that Nomar Garciaparra once occupied the same rarefied air as Martinez is now a largely forgotten footnote to a pre-championship era in Red Sox history.

Boston atop a baseball Olympus. For a time, Martinez enjoyed a peer whose performances nearly matched the pitcher for brilliance. Yet the fact that Nomar Garciaparra once occupied the same rarefied air as Martinez is now a largely forgotten footnote to a pre-championship era in Red Sox history.

Indeed, on a day when Martinez garnered more than 91 percent of votes from eligible members of the Baseball Writers Association of America for a landslide first-ballot election, Garciaparra just barely gleaned the 5 percent of votes needed to stay on the ballot beyond his first year of eligibility. In the late-1990s, the idea that Garciaparra wouldn’t even sniff the Hall of Fame seemed unfathomable.

He was as iconic a presence in many ways as Martinez, the stands at Fenway Park blanketed in equal measure by fans wearing No. 5 and 45, a shared tribute to the pitcher with boundless self-confidence based on an unmatched pitch mix and the shortstop with a million superstitions and quirks, who winged the ball across the diamond with a signature cross-body, sidearm delivery and who displayed a preternatural ability to hit the snot out of the ball.

Garciaparra was a force like few others in the game’s history. Between 1997 and 2003 – when he amassed a Rookie of the Year trophy, finished in the top five in AL MVP voting five times (topping out at second in 1998), made five All-Star teams, won consecutive batting titles with marks of .357 and .372 in 1999 and 2000 (becoming the first righthanded hitter to win back-to-back batting titles since Joe DiMaggio) – he donned the mantle of greatness.

“From 1997 to 2003, Nomar offensively, in the batter’s box, was just a different animal than most. It screamed Hall of Famer,” said Garciaparra’s former teammate and current WEEI radio host Lou Merloni. “In 2000, I’ve never seen anyone barrel up balls on the consistent basis he did that year. That was the most legit .372 I’ve ever seen in my life.

“He would go 2-for-5 with two lineouts. It was ridiculous. As far as the barrel-up rate, it was probably more like 75 percent of the balls he hit were on the barrel. It was just preposterous what he did that year. Everybody watching him would say the same exact thing: ‘I’ve never seen a guy barrel up the ball more than him.’

“I’ve seen his bats. He’s very superstitious, but I’d see him go for a year with two or three bats. You’d pick one of them up, his gamer. The ball mark – he used brown maple – the ball mark, there wasn’t anything on the label and there wasn’t anything on the end of the bat. Everything was within probably three inches of the barrel, every single mark that the ball made on contact. You could tell he used it for about two months. … It was unbelievable.”

It was the sort of skill set that permitted Garciaparra to commune with baseball legends. Ted Williams was mesmerized by the shortstop, believing that he possessed the skills to become his successor as a .400 hitter, a player who hit for average, displayed 30-homer power and a skilled baserunner who often delivered double-digit stolen base totals.

“Nomar was a uniquely gifted player, a six-time All-Star and two-time batting champ. He followed another great righthanded hitter, Joe DiMaggio. That’s an extreme, unique combination, plus he played a skill position at shortstop,” recalled Orioles GM Dan Duquette, who occupied the same role with the Red Sox for most of Garciaparra’s big league tenure in Boston. “He had all the skills [to be a Hall of Famer]. He got to the big leagues quickly, won the Rookie of the Year, won a couple of batting titles early in his career. It was just a matter of whether he could stand the test of time.”

“Nomar was a uniquely gifted player, a six-time All-Star and two-time batting champ. He followed another great righthanded hitter, Joe DiMaggio. That’s an extreme, unique combination, plus he played a skill position at shortstop,” recalled Orioles GM Dan Duquette, who occupied the same role with the Red Sox for most of Garciaparra’s big league tenure in Boston. “He had all the skills [to be a Hall of Famer]. He got to the big leagues quickly, won the Rookie of the Year, won a couple of batting titles early in his career. It was just a matter of whether he could stand the test of time.”

He couldn’t, of course. Though Garciaparra came back in startling fashion from a 2001 season lost largely to wrist surgery with a pair of All-Star campaigns in 2002 and 2003, he suffered an Achilles injury during spring training in 2004 that set in motion both the end of his Red Sox career and represented the starting point of a late-career crumble.

Still, on a day that could have marked a formal closing of Cooperstown’s doors to him, it’s worth remembering a time when it seemed like Garciaparra was going to knock on the Hall’s gates, to remember a Hall of Fame-caliber peak that lacked the requisite longevity for enshrinement.

Garciaparra had an .882 career OPS, the best of all-time by a shortstop who spent at least half his career at the game’s most demanding position with at least 5,000 career plate appearances. How good is an .882 OPS for a shortstop? It’s better than Hall of Fame shortstops Arky Vaughan (.859), Honus Wagner (.858), Joe Cronin (.857), Barry Larkin (.815), Hughie Jennings (.797), Lou Boudreau (.795),Cal Ripken (.788) and Robin Yount (.772). Derek Jeter achieved an .882 OPS in just three of his 20 seasons.

Of course, league context is important, since Garciaparra thrived during the Nintendo Numbers era. But even relative to his league, he stood out from most of the Hall of Fame pack as measured by OPS+ (OPS relative to the league average, adjusted for parks, in which a 100 OPS+ is average). Among Hall of Fame shortstops, Garciaparra ranks only behind Wagner (151 OPS+) and Vaughan (136 OPS+), well ahead of Larkin (116), Jeter (115), Yount (115), Ripken (112) and Alan Trammell (110).

The crux of Garciaparra’s irrelevance in the Hall of Fame conversation is the brevity of his stardom. He was a singular force from 1997 to 2003, but while he remained a passably productive hitter after that peak, posting a .291/.343/.446 line with a roughly league-average OPS+ of 102, he averaged just 84 games over the last six years of his career from 2004-09.

He fell off a cliff rather than enjoying a gradual decline, and ended his career with just 6,116 plate appearances. There are position players in the Hall of Fame with fewer plate appearances, but none who played after 1957 (the last season of three-time MVP Roy Campanella’s career). His 44.2 career WAR (as tabulated by Baseball-Reference.com) wouldn’t be the lowest ever by a position player with a plaque in Cooperstown, but no position player who has played since Bill Mazeroski (retired in 1972 with 36.2 WAR) has been enshrined.

Still, the cavalier dismissal of his Hall of Fame case (particularly in light of the 10-vote limit at a time when a PED-era traffic jam has created an electoral mess) belies the time when Garciaparra clearly represented one of the game’s greats, when he and Pedro represented the same sort of first-name luminaries in Boston and the game.

“I knew when I was playing against a Hall of Famer or playing with one. It was just a step above. And there’s no question that he was that,” said Merloni. “If he had two more Nomar-type years and maybe a couple more after [2003], or three more years, I don’t think there’s a question that he’s a Hall of Fame-type of talent. There’s no question that he was a Hall of Famer in his heyday. He just wasn’t there long enough.”

“I knew when I was playing against a Hall of Famer or playing with one. It was just a step above. And there’s no question that he was that,” said Merloni. “If he had two more Nomar-type years and maybe a couple more after [2003], or three more years, I don’t think there’s a question that he’s a Hall of Fame-type of talent. There’s no question that he was a Hall of Famer in his heyday. He just wasn’t there long enough.”

The fact that his career won’t conclude in the Hall does not diminish the idea that Garciaparra enjoyed a historic start to his career. And at a time when Martinez rightly will take his bows, it’s worth remembering the teammate whose career once merited an almost-equal measure of awe, and whose not-quite-Hall-worthy career now stands as a monument to the great separator of durability and longevity.

It’s a New Year! Maybe it’s time to elect some starting pitchers to Cooperstown?

Curt Schilling appeared on the Hall of Fame ballot for the first time a year ago with overwhelmingly strong credentials for election: The 216-game winner ranks 26th all-time in wins above replacement for pitchers (17th-highest total since the live ball era began in 1920) and 15th all-time in strikeouts, including three 300-strikeout seasons; he’s got the best strikeout-to-walk ratio of any pitcher ever (well, not counting a guy named Tommy Bond who was 5-foot-7, born in Ireland and began his career with the 1874 Brooklyn Atlantics) and three 20-win seasons; and he led the league twice in wins, twice in innings, three times in starts, four times in complete games (his 15 complete games in 1998 is the highest total in the majors since 1991), twice in strikeouts and five times in strikeout-walk ratio. Schilling never won a Cy Young Award but finished second in the voting three times.

Curt Schilling appeared on the Hall of Fame ballot for the first time a year ago with overwhelmingly strong credentials for election: The 216-game winner ranks 26th all-time in wins above replacement for pitchers (17th-highest total since the live ball era began in 1920) and 15th all-time in strikeouts, including three 300-strikeout seasons; he’s got the best strikeout-to-walk ratio of any pitcher ever (well, not counting a guy named Tommy Bond who was 5-foot-7, born in Ireland and began his career with the 1874 Brooklyn Atlantics) and three 20-win seasons; and he led the league twice in wins, twice in innings, three times in starts, four times in complete games (his 15 complete games in 1998 is the highest total in the majors since 1991), twice in strikeouts and five times in strikeout-walk ratio. Schilling never won a Cy Young Award but finished second in the voting three times.

Of course, Schilling was also one of the greatest postseason pitchers ever, going 11- 2 with a 2.23 ERA in 19 starts. His October legacy includes his iconic Bloody Sock Game in Game 6 of the 2004 American League Championship Series against the Yankees, a win in the World Series that year that helped end the long suffering of Red Sox fans, plus his dominant performance throughout the 2001 postseason when he allowed six runs in six starts as the Diamondbacks won the World Series. He helped the Red Sox win another title in 2007. His career 3.46 ERA in a hitters’ era gives him an adjusted ERA equal to Tom Seaver and Bob Gibson and higher than Hall of Famers like Jim Palmer, Juan Marichal and Bob Feller.

2 with a 2.23 ERA in 19 starts. His October legacy includes his iconic Bloody Sock Game in Game 6 of the 2004 American League Championship Series against the Yankees, a win in the World Series that year that helped end the long suffering of Red Sox fans, plus his dominant performance throughout the 2001 postseason when he allowed six runs in six starts as the Diamondbacks won the World Series. He helped the Red Sox win another title in 2007. His career 3.46 ERA in a hitters’ era gives him an adjusted ERA equal to Tom Seaver and Bob Gibson and higher than Hall of Famers like Jim Palmer, Juan Marichal and Bob Feller.

Schilling was great, he has the advanced metrics that scream Hall of Famer, and he was an iconic figure in the game while active. What more do you need to get elected to Cooperstown?

More than 60 percent of voters didn’t check Schilling’s name on their ballot.

Then there’s the pitcher who finished with the same career adjusted ERA as Schilling. His best ERAs, all in seasons where he pitched more than 210 innings, were 1.89, 2.38, 2.39, 2.58 and 2.69, all coming when offensive totals were exploding. The worst of those seasons had an adjusted ERA+ of 150. Since 1920, only five other starters had five or more seasons with at least 200 innings and an ERA+ of 150 or higher: Greg Maddux, Roger Clemens, Lefty Grove, Randy Johnson and Roy Halladay. This pitcher had another season where he went 18-9 with a 3.00 ERA and another where he went 21-11 with a 3.32 ERA while leading his league in innings pitched. He won more than 200 games. He had a 16-strikeout game in the postseason. His career pitching WAR of 68.5 is higher than Palmer, Carl Hubbell or Don Drysdale.

Kevin Brown got 12 votes in his one year on the ballot, not close to the 5 percent needed to remain on the ballot, and he was kicked to the curb alongside Raul Mondesi, Bobby Higginson and Lenny Harris. Thank you for your nice career, but your case has no merit. Heck, Willie McGee received twice as many votes. I mean, Willie McGee was a nice player, and even a great one the season he won the MVP Award, but he had about half the career value of Brown.

Kevin Brown got 12 votes in his one year on the ballot, not close to the 5 percent needed to remain on the ballot, and he was kicked to the curb alongside Raul Mondesi, Bobby Higginson and Lenny Harris. Thank you for your nice career, but your case has no merit. Heck, Willie McGee received twice as many votes. I mean, Willie McGee was a nice player, and even a great one the season he won the MVP Award, but he had about half the career value of Brown.

The Baseball Writers’ Association of America treats starting pitchers like they’re infected with the plague. They’ve elected one in the past 14 years: Bert Blyleven in 2011. And Blyleven, despite winning 287 games and ranking 11th all-time in WAR among pitchers, took 14 years to finally get in. Meanwhile, the BBWAA has elected three relief pitchers in those 14 years, so it’s not an anti-pitcher bias; it’s an anti-starting pitcher bias.

What’s happened here? How come no starting pitcher who began his career after 1970 is in the Hall of Fame? Leaving aside the case of Clemens, who would have been elected if not for his ties to PEDs, there are several issues going on.

1. The 1980s were barren of strong, obvious Hall of Fame pitchers. The BBWAA ignored the cases of borderline candidates like David Cone (pictured below), Dave Stieb, Bret Saberhagen (pictured above) and Orel Hershiser, and instead embraced Jack Morris, a lesser pitcher than those four but a guy with more career wins.

2. Comparison to the previous generation of starters. Including Blyleven, there are 10 “1970s pitchers” in the Hall of Fame. Here they are, listed in order of election year along with each pitcher’s 10-year peak period:

Bert Blyleven (2011): 1971-1980 Nolan Ryan (1999): 1972-1981 Don Sutton (1998): 1971-1980 Phil Niekro (1997): 1970-1979 Steve Carlton (1994): 1972-1981 Tom Seaver (1992): 1968-1977 Fergie Jenkins (1991): 1967-1976 Gaylord Perry (1991): 1967-1976 Jim Palmer (1990): 1969-1978 Catfish Hunter (1987): 1967-1976

These pitchers aren’t merely just great pitchers but products of their generation. The late ’60s and early ’70s produced the lowest-scoring seasons in the major leagues since the dead ball era. The average team in 1968 scored 3.42 runs per game, the lowest total since 1908. That was the notorious pitchers’ year, but 1972 didn’t see much more offense at 3.69 runs per game. This was also the period when pitchers were worked harder than they had been in decades, making more starts and pitching more innings. The 15-year period from 1963 to 1977 saw 62 different seasons where a pitcher threw 300 innings. The previous 15 seasons saw it happen just 13 times (six by Robin Roberts); the ensuing 15 seasons saw it happen just three times, two of those by knuckleballer Niekro. This period was the perfect time to ferment long careers with lots of wins. More starts and more innings gave pitchers the opportunity to get more wins. It’s no coincidence that the peak seasons of the above pitchers all occurred in roughly the same time span.

3. Speaking of wins … Hall of Fame voters love wins like Yasiel Puig loves driving fast. Morris has 254, a main reason he earned 67.7 percent of the vote last year despite his 3.90 career ERA. Schilling has 216 and Brown 211. The fixation on career wins — and 300 in particular — is the result of a unique generation of pitchers; it’s a standard previous pitchers weren’t held to. Bob Gibson won 251 games, Juan Marichal 243, Whitey Ford 236, Don Drysdale 209 and Sandy Koufax 165. Focus on the entire résumé, not just the win total. Schilling didn’t win 254 games, let alone 300, but he’s a far superior Hall of Fame candidate to Morris.

Let’s compare Tom Glavine to Mike Mussina, both appearing on the ballot for the first time. With 305 wins, Glavine appears to be the much stronger candidate than Mussina, who won 270 games.

Here’s what one voter, Dan Shaughnessy of The Boston Globe, wrote:

Glavine and Maddux were 300-game winners. Those are magic plateaus … unless you cheated.

The rest of the list of players I reject are good old-fashioned baseball arguments. (Craig) Biggio got 68.2 percent of the vote last year, but I don’t think of him as Hall-worthy (only one 200-hit season). Same for Mussina and his 270 wins (he always pitched for good teams) and (Lee) Smith and his 478 saves (saves are overrated and often artificial).

There you go. Glavine won 305 games, Mussina won 270, so Glavine is the easy choice. As an aside: I love the bit about Mussina pitching for good teams. As if Glavine didn’t pitch for good teams? Since when is pitching for good teams considered a demerit?

Plus, as Jason Collette pointed out, “Mussina pitched for Baltimore for 10 years — and Baltimore had losing records in five of those ten seasons. Yet, Mussina had a .645 winning percentage and won 147 of his 270 starts with the Orioles. The Yankees never had a losing record when Mussina pitched there and he had a .631 winning percentage with them. Mussina’s .645 winning percentage as an Oriole dwarfed the team’s .510 winning percentage in that same time.”

(Also, Shaughnessy is apparently voting for Morris because he won 254 games, which I believe is less than 270.)

Anyway, when you examine the numbers a little deeper, Glavine and Mussina compare favorably:

Pitching WAR

- Glavine: 74.0

- Mussina: 82.7

ERA+

- Glavine: 118 (3.54 career ERA in the National League with great defense behind him)

- Mussina: 123 (3.68 career ERA in the American League with often bad defenses behind him)

5+ WAR seasons

- Glavine: 4

- Mussina: 10

Postseason

- Glavine: 14-16, 3.30 ERA, 1.27 WHIP

- Mussina: 7-8, 3.42 ERA, 1.10 WHIP

The point here isn’t to detract from Glavine, but that Mussina has every bit the case Glavine does — or 95 percent of it, giving Glavine some extra credit if you wish for his two Cy Youngs. Glavine hung on and won 35 more games; Mussina retired after winning 20. That doesn’t make Glavine a superior pitcher.

4. Stingy voters. To a certain extent, the BBWAA voters have become tough on all candidates — not just starting pitchers and PED users.

As Joe Sheehan wrote recently:

Consider the recent history of Hall voting. The average number of players named per ballot declined steadily up until just last year. In 1966, which was the first vote in the modern era of BBWAA balloting (that is, in which there have been no years in which the BBWAA did not vote), there were 7.2 names listed per ballot. Ten years later, that figure was 7.6. By 2000, a year that featured two players voted in and a ballot with five others who would eventually be voted in (plus Jack Morris, still kicking around), the number was down to 5.6. There were more baseball players than ever before becoming eligible for the Hall, but the voters were becoming much more difficult to impress. That would remain the case for most of this century:

2001: 6.3 2002: 6.0 2003: 6.6 2004: 6.6 2005: 5.6 2007: 6.6 2008: 5.4 2009: 5.4 2010: 5.7 2011: 6.0 2012: 5.1 2013: 6.6

Remember, that downward trend is occurring despite an increasingly crowded ballot due to the split opinions on what do about the PED candidates. With as many as 15 to 20 legitimate Hall of Fame candidates on this year’s ballot it will be interesting to see if that 6.6 players per ballot increases further.

5. Timing. The starting pitching problem will be abated somewhat in upcoming elections. Maddux will get in this year, Glavine this year or next. Randy Johnson, Pedro Martinez (pictured above) and John Smoltz (pictured below) then join the ballot next year. Johnson is a lock, and Martinez has the Koufax-esque peak value thing going for him, although with 219 wins he’s not a first-year lock. Smoltz is similar to Schilling in many ways, down to the career win total (213) and postseason heroics, so odds are he’ll face the same uphill climb.

I believe most Hall of Fame voters have the same goal: Elect the best players to the Hall of Fame, or at least the best ones they believe to be clean from PEDs. That issue is still stuck in the mud, the Hall itself refusing to give guidance to the voters. But electing Curt Schilling and Mike Mussina is simply an issue of understanding their greatness. They are among the very best pitchers in the history of the game. They deserve to be elected this year, alongside Maddux and Glavine.

Big Papi defined the term ‘sportsman’…

From: Scoop Jackson – ESPN

David Ortiz spoke with his bat, but it was his words that won the World Series

Boston Red S ox savior David Ortiz’s path to World Series MVP and my pick for sportsman of the year began on April 20. During a ceremony before a baseball game in front of his city, inside of his park, he grabbed a microphone and said these five words: “This is our fucking city!”

ox savior David Ortiz’s path to World Series MVP and my pick for sportsman of the year began on April 20. During a ceremony before a baseball game in front of his city, inside of his park, he grabbed a microphone and said these five words: “This is our fucking city!”

From that moment forward, David Ortiz became a symbol of hope, pride, strength and resilience for a city that was in need of something more than baseball to heal the pain it was struggling through.

Now all it needed was a hero.

Bats speak louder than words.

That’s what true baseball historians, aficionados, legends and lifers will tell you if you ever get into a real conversation with them about the importance of the game and the role it’s played in this country.

The game’s association with apple pie and Chevys is minimal and almost degrading. The game, when put in proper perspective, is so much larger. Pies get eaten, cars get driven. Bats create sounds and produce runs. They feed souls and drive spirits. And those who swing bats — and swing them well — have always had voices that have the power to go beyond the impact their hits can have inside the diamond.

Somehow, Ortiz used the six months following the Boston Marathon bombing to let his bat speak. To back up the words he spoke on that horrific day.

He was able to take a team (and organization) that had just had one of the worst seasons in its 112-year history and ignite a resurrection rarely seen in modern-day sports.

At 37 years old and in his 16th year in baseball (11th with the Red Sox), his .309, 30 HRs, 103 RBIs, .395 OPB stat line was the omphalos, the center point, of a remarkable turnaround. In 2012, the team finished with 93 losses. In July, the Sox were 20 games over .500 and took back first place in the American League East by the end of the month. They never looked back.

His numbers in the World Series did more than speak for themselves. Still two months after the fact it is difficult to comprehend what Ortiz did between the Wednesdays of Oct. 23 and 30.

Before the final game of the World Series, Ortiz was hitting .733 with a slugging percentage of 1.267 in the first five games. His 11 hits at the time were two shy of the most ever in a World Series and he still had two more possible games to play; they accounted for a third (11 of 33) of the total team hits. And this is without the first-at-bat grand slam that St. Louis’ Carlos Beltran robbed him of in Game 1. Add that to the list and Reggie Jackson loses his “Mr. October” nickname and his legacy is no longer as mythical and untouchable as it’s been made out to be.

The media dubbed Ortiz “King of October,” while his teammates began calling him “Cooperstown.”

Ortiz’s final World Series math added up to him having a .688 BA, .760 OBP, 1.188 SLG with eight walks (a Series record), two HRs and six RBIs. His final postseason math for 2013 was .353, .500 OBP, .706 SLG. More telling: His World Series OPS was 1.948 while the team’s was .484.

When a player hits almost .700 in a championship round and the rest of his team hits below .179 and that team still wins it all, it becomes appropriate to for that moment spell team with an “i.”

“I would be doing him a disservice trying to put it into words,” Red Sox GM Ben Cherington told reporters after the World Series. “He just keeps writing new chapters. I know great players are great, are more likely to be great in any moment, but it’s hard to see him in those moments and not think that there’s something different about him. He’s locked in. We’ve seen him locked in before, but to do it on this stage, and do it in so many big moments, I can’t add anything more to the legend that’s already there, but he keeps writing more chapters on his own.”

But it was the chapter he wrote in the dugout of Game 4 that elevated his team, Red Sox Nation and his own stature. It was a pivotal, Series-changing moment. With Boston down 2-1 in the Series, Game 4 was tied at 1 going into the sixth inning and Ortiz — not his bat — decided to speak.

“It was like 24 kindergartners looking up at their teacher,” said teammate Jonny Gomes, who moments after Ortiz’s speech hit a three-run game-winning homer. “He got everyone’s attention, and we looked him right in the eyes. That message was pretty powerful.”

In his own way, as only he could, Ortiz told his team to just do what he was doing: Play ball. Simple. “I know we are a better team than what we had shown. Sometimes you get to this stage and you try to overdo things, and it doesn’t work that way,” he remembers saying.

And afterward, whether it was sitting with his son, the World Series MVP trophy and Chris Berman on the field or in a studio chopping it up with David Letterman, Ortiz came off as the one athlete for whom moments like this were born.

A marriage of performance and personality. The mastering of craft and class. All along, when everything was supposed to be about him, about what he had just accomplished, Ortiz never ventured or leaned away from keeping this entire experience about — and for — Boston.

He put the victims and people affected by the bombing ahead of himself. He reminded us all along the way that while the game itself cannot change lives or save them, a sense of freedom can come through the swing of a bat. It can lift the souls of fans and in this case a city.

I’m not the first to suggest Big Papi as sportsman of the year. Sports Illustrated’s Tom Verducci suggested it as well. I hope we are not alone.

The sublimeness of sports rests in the fact that no one sees something like this coming. No one at the beginning of 2013 could have told you that David Ortiz would elevate himself and the Boston Red Sox and the city of Boston (almost) single-handedly within a span of eight months. Especially someone who started off the season on the disabled list.

“Baseball deludes us,” Cal Fussman once wrote. “The crack of the bat, the majestic flight of the ball, the slow, regal trot around the bases. We rise to our feet and roar. We think we are seeing power.”

He started the next paragraph to open the final chapter of “After Jackie” with, “But we’re not.”

But sometimes, even in baseball, we witness something more.

After Ortiz released his infamous and FCC excused and approved “f-bomb” on Boston’s field of hopes and dreams, the words that followed were this: “And nobody’s going to dictate our freedom. Stay strong.”

Sometimes, even when a bat is making a historic amount of noise, words can speak louder.

HOF Double Standards? Who’d have thought….

From: Ann Killion of the SFGate

The Baseball Hall of Fame ballots are due at the end of the month and the process just got more confusing than ever.

Steroid players? Still unlikely to be voted in.

Steroid managers? That’s a different story.

The Boys of Steroids are still on the Boys of Summer ballot: Barry Bonds, Roger Clemens, Sammy Sosa, Mark McGwire and Rafael Palmeiro are among the 36 players on the 2014 ballot. They’re all there to be accepted or – more likely – rejected by the majority of the 500-plus Baseball Writers’ Association of America voters who participate (I’m one of those voters).

Last year, none of the players who come with substantial evidence that they used steroids received more than 37.6 percent of the vote. They need 75 percent of the votes to be inducted. Last year not a single player was voted into the Hall of Fame, making for a muted ceremony that probably contributed little to the Cooperstown economy.

Players stay on the ballot for 15 years, so this issue is far from over. However, it takes a lot of mind-changing – and a long time – for a player to jump almost 40 percentage points in balloting.

So all of those players must look at what just happened with the Expansion Era Committee voting last weekend and feel puzzled. Three of the best, most successful managers of the steroid era were elected unanimously: Joe Torre, Bobby Cox and – most notably – Tony La Russa. Easy, quick, no fuss.

If there were an all-steroid baseball team (Bonds in left, McGwire at first, Clemens on the mound – we can keep going), there’s no doubt who the manager would be. It would be La Russa, who managed the A’s in the late ’80s and early ’90s Bash Brothers era, widely considered Ground Zero for rampant steroid use. Then La Russa went on to manage the St. Louis Cardinals, where McGwire made it fashionable to use steroids to break baseball’s most hallowed records.

If there were an all-steroid baseball team (Bonds in left, McGwire at first, Clemens on the mound – we can keep going), there’s no doubt who the manager would be. It would be La Russa, who managed the A’s in the late ’80s and early ’90s Bash Brothers era, widely considered Ground Zero for rampant steroid use. Then La Russa went on to manage the St. Louis Cardinals, where McGwire made it fashionable to use steroids to break baseball’s most hallowed records.

Along the way to this week’s Hall of Fame vote, La Russa has been a hypocritical steroid-era bully, pointing fingers at and calling out players he didn’t like, even ones he managed, such as Canseco, while simultaneously angrily defending McGwire and others. He eventually hired McGwire as his hitting coach in a transparent attempt to improve the slugger’s Hall of Fame chances. That backfired: McGwire’s vote tallies actually continue to drop. La Russa has both claimed that everyone knew Canseco was on steroids and to have no knowledge that McGwire was juicing. La Russa has attacked every reporter or outsider who dared to raise the issue.

steroid-era bully, pointing fingers at and calling out players he didn’t like, even ones he managed, such as Canseco, while simultaneously angrily defending McGwire and others. He eventually hired McGwire as his hitting coach in a transparent attempt to improve the slugger’s Hall of Fame chances. That backfired: McGwire’s vote tallies actually continue to drop. La Russa has both claimed that everyone knew Canseco was on steroids and to have no knowledge that McGwire was juicing. La Russa has attacked every reporter or outsider who dared to raise the issue.

But he, along with Torre and Cox, was unanimously elected inside a hotel room in Orlando by 16 voters on the Expansion Era Committee. The Chronicle’s Bruce Jenkins was one of those voters and is sworn to absolute secrecy about the details of the process. But he did describe a closed-door environment where “everyone spoke the same language,” and held old-school values, removed from “the complex lingo of new-age stat devotees.”

I’m sure that the discussion of how the candidates benefited from steroids, if it was raised at all, took a back seat to all the other accomplishments in the candidates’ resumes. The managers elected were certainly helped by the belief that everyone was looking the other way. Of course those same arguments could and have been made on behalf of the steroid-era players on the ballot, and – for now – have been rejected by voters.

So would the steroid-tainted players benefit from getting into that exclusive kind of Expansion Era Committee environment – which they eventually may if they aren’t inducted while on the active ballot? Don’t be so sure. The most vocal opponents of steroid use are the men who have made it into the Hall of Fame. They believe their game and legacy has been tainted (and probably want to keep the Hall of Fame as exclusive as possible). Men such as Frank Robinson, Rod Carew and Andre Dawson who were on this year’s committee all have publicly damned steroid use. A 75 percent threshold would be hard to reach without the former players.

And the committee isn’t likely to embrace the old argument for letting in steroid users, that “you can’t write the history of baseball without them.” After all, they just rejected union leader Marvin Miller, whose contributions are significant to baseball history. Miller, of course, was instrumental in keeping drug testing out of the game for so long.

The process is muddied on so many levels. ESPN commentator Keith Olbermann had an interesting rant about La Russa’s election, noting that Pete Rose is banned from the ballot for betting while managing, which might have caused an unfair and illegal advantage to opponents, while “Tony La Russa was manager of the Founding Fathers of modern PED use who, because of their unfair and illegal advantage, doubtless won games they were not supposed to win.”

Sigh. It’s an honor. It’s a puzzle.

The Veterans Committee Ballot is Missing It’s Top Candidate…

The Veterans Committee portion of the Hall of Fame induction process doesn’t generate the same uproar as the Baseball Writers vote does. But the people it elects are still full-fledged members of Cooperstown, with their little plaques right there next to Hank Aaron, Willie Mays and Babe Ruth. Last year, the Veterans Committee elected an owner, an umpire and a player — all of whom had been dead since 1939.

This year, the committee is looking at what it calls the Expansion Era ballot, for candidates whose greatest contributions came in 1973 and later. The last time the VC looked at this era, in 2011, only executive Pat Gillick was elected. This year’s ballot will likely produce more Hall of Famers; sadly, however, none are likely to be players. The 12 finalists who the 16-man committee (and it’s all men, no women) will consider includes six players and six others. You need 12 of 16 votes to get elected. Let’s take a closer look.

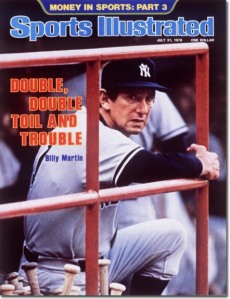

The managers: Bobby Cox, Tony La Russa, Billy Martin, Joe Torre

Even by the historically lax standards of the Veterans Committee, Cox, La Russa and Torre are obvious Hall of Fame managers, and I suspect all three will get in. Cox is fourth on the all-time wins list and made 16 playoff appearances with the Blue Jays and Braves, although he won just one World Series. Cox finished 503 wins above .500 — the only managers with a higher total are John McGraw and Joe McCarthy. You can hold the the only-one-title against Cox, but Whitey Herzog made it in 2010 with just one title, fewer wins and a worse winning percentage. La Russa is third on the all-time wins list and has three World Series titles. Torre had a borderline Hall of Fame career as a player; include his four championships as a manager and he’s the third lock.

Martin is the interesting candidate, but he has no chance to get in with this group also on the ballot. Martin is 35th on the wins list and won just one title. What we do know about him, however, is that he was arguably the best turn-around artist in managerial history. Now, part of that was because nobody could stand to have him as their manager for more than five minutes, so he got a lot of opportunities. But consider:

- Took over the Twins in 1969 and they improved from 79 to 97 wins and won the AL West. (Fired after the season, in part for getting in a fight with one of his pitchers.)

- Took over the Tigers in 1971 and they improved from 79 to 91 wins. In 1972, they won the AL East. (Fired in 1973 after ordering his pitchers to throw spitballs in protest of Gaylord Perry allegedly doing so for Cleveland.)

- Took over Rangers in September of 1973. The club improved from 57-105 to 84-78 in 1974. (Fired in 1975 after a confrontation with owner Brad Corbett.)

- Took over the Yankees late in 1975. Club improved from 83 wins to 97 in ’76 and won its first pennant since 1964. In 1977, the Yankees won the World Series. (Resigned in 1978 after fighting with Reggie Jackson during a game and rumors that George Steinbrenner tried to trade Martin to the White Sox.)

- After managing the Yankees again for part of the 1979 season, he took over the A’s in 1980. They had lost 108 games in 1979. They won 83 and then made the playoffs in the strike season of 1981. (Fired after losing 94 games in 1982.)

Then came all the ridiculousness with the Yankees in the ’80s. Still, it’s an impressive track record, although it came at a cost: Martin overworked his pitchers (most notably with a young staff in Oakland that soon fell apart) and none of the teams he managed sustained any long-term success. In the end; not enough career wins, only one title and his other issues (drinking and brawling) that might have affected his teams. Plus: We have enough managers in already, with three more on the way.

The owner: George Steinbrenner

The Boss was on the last Expansion Era ballot and received fewer than eight votes. He was a bully, banned from baseball for paying a gambler to dig up dirt on Dave Winfield, and ran the franchise into the ground in the late ’80s and early ’90s (only to see it revived during his banishment). His team also won six World Series titles (and a seventh after he had given up day-to-day operations to his sons), and there’s no denying he was one of the most famous people in the sport during his reign. No Thanks, I’ll pass, but there’s definitely an argument to put him in.

The union guy: Marvin Miller

Miller fell one vote short of election last time around. Since then, he passed away and you almost feel as though the time to honor the man was missed. He’s no doubt one of the most important figures in baseball history; the union leader who helped free the players from the reserve clause and enter the era of free agency. Does that make him a Hall of Famer? Nobody ever paid a penny to watch Marvin Miller in action. But if you can vote in Bowie Kuhn, you should put in Marvin Miller. FYI: There are four executives on the committee (Paul Beeston, Andy MacPhail, Dave Montgomery and Jerry Reinsdorf), so if they all vote against him, the other 12 (which includes six Hall of Fame players) have to vote for him.

Miller fell one vote short of election last time around. Since then, he passed away and you almost feel as though the time to honor the man was missed. He’s no doubt one of the most important figures in baseball history; the union leader who helped free the players from the reserve clause and enter the era of free agency. Does that make him a Hall of Famer? Nobody ever paid a penny to watch Marvin Miller in action. But if you can vote in Bowie Kuhn, you should put in Marvin Miller. FYI: There are four executives on the committee (Paul Beeston, Andy MacPhail, Dave Montgomery and Jerry Reinsdorf), so if they all vote against him, the other 12 (which includes six Hall of Fame players) have to vote for him.

The glove: Dave Concepcion

Concepcion received eight votes in 2010, so he is the highest returning player candidate. With a career WAR of 40.0, he doesn’t have a strong statistical argument. There is also another shortstop candidate with obviously better credentials: Alan Trammell, who is still on the BBWAA ballot. Concepcion’s case basically comes down to being part of the Big Red Machine, although he was a nine-time All-Star and won five Gold Gloves. The Reds already have one marginal Hall of Famer in Tony Perez; We don’t need another.

The strong jaw: Steve Garvey

He was also on the last ballot and received fewer than eight votes. Career WAR of 37.6, only one season above 5.0. His case is that he was regarded as very valuable while active — he won an MVP Award and finished second another year and sixth three other times. It’s kind of a Jim Rice argument. Won’t get in as Keith Hernandez would be a better candidate to discuss at first base.

The guy they named the surgery after: Tommy John

Three pitching lines:

John: 288-231, 3.34 ERA, 111 ERA+, 62.3 WAR

Bert Blyleven: 287-250, 3.31 ERA, 118 ERA+, 96.5 WAR

Jack Morris: 254-186, 3.90 ERA, 105 ERA+, 43.8 WAR

Three pitchers with similar career win-loss records, but vastly different values by Wins Above Replacement. All three got about 20 percent of the vote their first years on the BBWAA ballot. Blyleven stayed there for a long time until the statistical argument became clear that he deserved Cooperstown; score one for the statheads. Morris has slowly climbed closer to 75 percent and may get in this year; score one for the old schoolers. John never really moved from his initial 22 percent.

Three pitchers with similar career win-loss records, but vastly different values by Wins Above Replacement. All three got about 20 percent of the vote their first years on the BBWAA ballot. Blyleven stayed there for a long time until the statistical argument became clear that he deserved Cooperstown; score one for the statheads. Morris has slowly climbed closer to 75 percent and may get in this year; score one for the old schoolers. John never really moved from his initial 22 percent.

By WAR, John is in the gray area; a good candidate but not a strong one. The argument against him is that he pitched forever but was never great. His peak WAR season was 5.6 and he had four years above 5.0. But just four others above 3.0. A lot of 2.4 and 1.5 kinds of seasons. Good No. 3 starter who was durable but rarely an ace. I wouldn’t vote for him, although Blyleven’s election in 2011 may help him.

The Cobra: Dave Parker

Parker is new to the ballot, with Al Oliver, Rusty Staub, Ron Guidry and Vida Blue getting bumped off. Parker has some interesting career numbers: .290 average, 339 home runs, 1,439 RBIs, more than 2,700 hits. He won an MVP Award in 1978 and deserved it. He had a very high peak from 1975 to 1979, but then wasted several years and wasn’t really contributing much after that despite his high RBI totals.

Parker is new to the ballot, with Al Oliver, Rusty Staub, Ron Guidry and Vida Blue getting bumped off. Parker has some interesting career numbers: .290 average, 339 home runs, 1,439 RBIs, more than 2,700 hits. He won an MVP Award in 1978 and deserved it. He had a very high peak from 1975 to 1979, but then wasted several years and wasn’t really contributing much after that despite his high RBI totals.

Is Parker the best outfielder not in the Hall of Fame? Clearly not. Even leaving off all the players still on the BBWAA ballot, there’s another right fielder I would have preferred to see on this ballot: the criminally underrated Dwight Evans.

Evans is sort of the opposite of Parker. Parker had his best years in his 20s; Evans in his 30s. Parker never walked; Evans built a lot of value by walking (708 more career walks). Parker got fat; Evans stayed in tremendous shape. Parker ended up wasting a lot of his ability; Evans got the most out of his.

By career WAR, it’s not close: Parker 40.0, Evans 66.7. Let’s get Dewey on the ballot next time.

The submariner: Dan Quisenberry

His career wasn’t really so different from Bruce Sutter’s, except Sutter had more facial hair and “invented” a pitch. Consider Quisenberry’s run in Cy Young voting: fifth, no votes (1.73 ERA, though), third, second, second, third. He also finished in the top 10 of the MVP voting in four of those seasons. That said … voters of that era dramatically overrated relief pitchers, even though they were pitching a lot more innings than today. But for a six-year run, he was as good as anybody.

The catcher: Ted Simmons

He’s back after receiving fewer than eight votes. One of the better hitting catchers, with a .285 career average (hit above .300 seven times), 248 home runs and 1,389 RBIs. He played second fiddle to Johnny Bench in the National League in the 1970s but, hey, not everybody can be Johnny Bench.

Two of the people on the committee are Paul Molitor, Simmons’ teammate with the Brewers, and Whitey Herzog, who traded Simmons from the Cardinals to the Brewers after the two feuded and Simmons’ defense had started declining. So one could see Molitor arguing for Simmons and Herzog against Simmons.

Either way, it probably doesn’t matter, as Simmons’ chances of getting in are slim.

The results will be announced at the winter meetings in December.